The most significant flavor of carbonated drinks, including cola, is undoubtedly their sweetness. This sweetness primarily comes from sugar or high-fructose corn syrup. For instance, a 250mL serving of cola contains 28 grams of sugar, which accounts for all the calories in the beverage. Interestingly, the type of sweetener used in the world’s number one cola brand, Coca-Cola, varies by country. In the United States, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), derived from corn, is used. In Korea (of course South Korea), a mix of sugar and HFCS is used. The cola considered the best by cola enthusiasts, Coca-Cola sold in Japan use only sugar to achieve their sweet taste. Japan has stricter regulations regarding the use of natural ingredients in foods. Mexican Coca-Cola also uses only sugar (though this is now done mainly for export). The reason Mexican Coca-Cola traditionally used only sugar was to protect the country’s sugar cane industry from the massive influx of HFCS produced and exported by the United States.

Sugar is a disaccharide composed of glucose and fructose. It is said to taste less sweet than pure glucose. In our bodies, sugar is broken down into glucose and fructose. Glucose is used as an immediate energy source, while fructose, although it doesn’t raise blood sugar levels as quickly as glucose, is eventually converted into glucose in the liver and used as energy. Regardless of the type of sugar, consuming large amounts is not healthy.

Does the high sugar content make cola a prime example of an unhealthy drink? According to a 2015 report by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety, the average sugar content per serving size is as follows: carbonated drinks ~24 g, fruit and vegetable juices ~20 g, fruit and vegetable drinks ~17 g, mixed drinks ~15 g, and yogurt drinks ~11 g, indicating that all these beverages contain significant amounts of sugar. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that adults limit their sugar intake to less than 10% of their total energy intake, which translates to less than 50 g of sugar per day. Based on this guideline, drinking one can (8 oz) of carbonated beverage per day should not pose a major health risk.

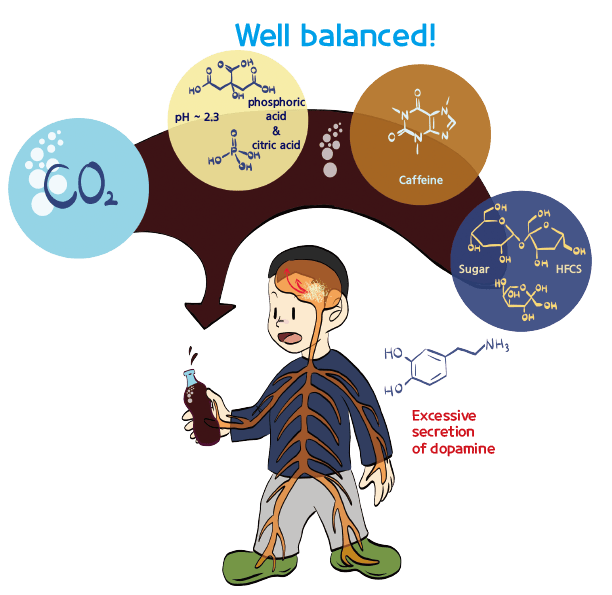

Various media point out that the problem with soft drinks is their addictive nature, attributing caffeine as the main cause of this addiction. Drug addiction is defined as 1) a state where one cannot control the use or amount of a drug, or 2) a state where one experiences severe negative emotions when unable to use the drug. This condition occurs because the consumption of the addictive substance triggers an excessive release of dopamine, a neurotransmitter also known as the “happiness hormone,” which plays a crucial role in motor functions and the regulation of pituitary hormones. Caffeine can also activate the secretion of dopamine, leading to addiction. Additionally, caffeine interferes with the binding of a nucleic acid called adenosine to receptors in the nerve cell membrane. When adenosine is transmitted to nerve cells, it reduces neural activity and causes drowsiness. However, when caffeine binds to these receptors instead, it reactivates the nerves and makes one feel energized.

Many types of soft drinks contain caffeine. A 8 oz can of cola typically contains about 25 mg of caffeine. For adults, it is considered safe to consume up to 400 mg of caffeine per day. Compared to a cup of drip coffee, which can contain as much as 170 mg of caffeine, the amount in cola is relatively small, and even drinking ten cans a day would be acceptable. Consuming caffeinated beverages can enhance urinary function, leading to increased urination, but it is not enough to cause dehydration in a healthy adult.

So far, we have discussed the main components and their effects in cola and other soft drinks. Based on the ingredients and their concentrations, there doesn’t seem to be a reason to consider soft drinks harmful to health, nor do they appear likely to cause addiction. However, there is another point to consider: the definition of addiction. One symptom of drug addiction is the inability to control intake. Dr. Gary Wenk, a neuroscientist and author of “Your Brain and Food,” analyzes that the addiction to soft drinks stems from their being “designed to make consumers feel good due to the right amounts of sugar, caffeine, and carbonation.” Thus, it is not a specific substance that causes addiction but the combination of all added ingredients that makes consumers continue to enjoy them lightly and feel good, leading to uncontrolled consumption.

While adults can consume significant amounts of carbonated beverages without major issues, the situation is different for minors. For those under 18, it is recommended to limit sugar intake to less than 25 grams per day. Regarding caffeine, children under 12 should avoid it entirely, and those aged 12 to 18 should limit their intake to no more than 100 mg per day. A single can of cola contains more sugar than the recommended daily limit for minors and includes caffeine, which is prohibited for children under 12. Particularly, children, who have more difficulty controlling impulses compared to adults, can become more easily addicted to the pleasant sensation provided by carbonated drinks. Therefore, adult supervision and intervention are crucial in preventing children from developing an addiction to these beverages.

Overdoing something can be worse than not doing it at all. This concept is highly relevant in biochemistry. A physician and early chemist, Paracelsus (1493-1541), famously stated, “All things are poison, and nothing is without poison; the dosage alone makes it so a thing is not a poison.” Carbonated drinks, once beloved for their refreshing qualities, have become potentially harmful due to excessive consumption. This change illustrates the importance of moderation in all things.

References

- Skilling, Ask Tom: Does carbon dioxide released by soft drinks contribute to global warming?, Chicago Tribune, 2019. 02. 12

- Weinraub and Kelly, How ethanol plant shutdowns deepen pain for U.S. corn farmers, Reuters, 2019. 12. 13.

- Kelly and Baertlein, Beer may lose its fizz as CO2 supplies go flat during pandemic, Reuters, 2020. 04. 18.

- Reddy et al., J. Am. Dental Assoc. 2016, 147, 255

- http://www.nof.org/patients/treatment/nutrition/

- http://www.dietandfitnesstoday.com/phosphorus-in-orange-juice.php

- Larsen, (2009) ‘Erosion of teeth’ in Dental Caries: The Disease and Its Clinical Management. 2nd ed, Blackwell Munksgaard

- https://www.coca-colacompany.com

- Glusker, The Story of Mexican Coke Is a Lot More Complex Than Hipsters Would Like to Admit SMITHSONIAN magazine, 2015. 08. 11.

- Wiebe et al. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 123

- https://www.fda.gov/food

- WHO, (2015) Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children, WHO

- Koob and Simon, J. Drug Issues, 2009, 39, 115

- Volkow et al. Transl. Psychiatry, 2015, 5, e549

- Mayo Clinic Staff, Caffeine: How much is too much? Mayo clinic, 2020. 03. 06

- https://www.math.utah.edu/~yplee/fun/caffeine.html

- Drayer, What makes soda so addictive?, CNN health, 2019. 10. 28.

- Vos et al. Circulation, 2017 135, e1017

- Castle, Caffeine: a Growing Problem for Children, US News, 2017. 06. 01.

Leave a reply to Unveiling the Truth About Sugar in Fruit Juices – Leo & Leah Cancel reply