Hugh Kim & Soo Yeon Chae

We previously discussed the process up to separating peptides—derived from proteins extracted from cells or tissues using digestive enzymes—through liquid chromatography (LC). Although this explanation was simplified, each step in this process involves a wide array of techniques developed to extract the maximum amount of protein from the minimal amount of sample. There is active research being conducted on diagnosing diseases from just a drop of blood and analyzing the proteome of individual cells to identify environmental influences on cellular changes.

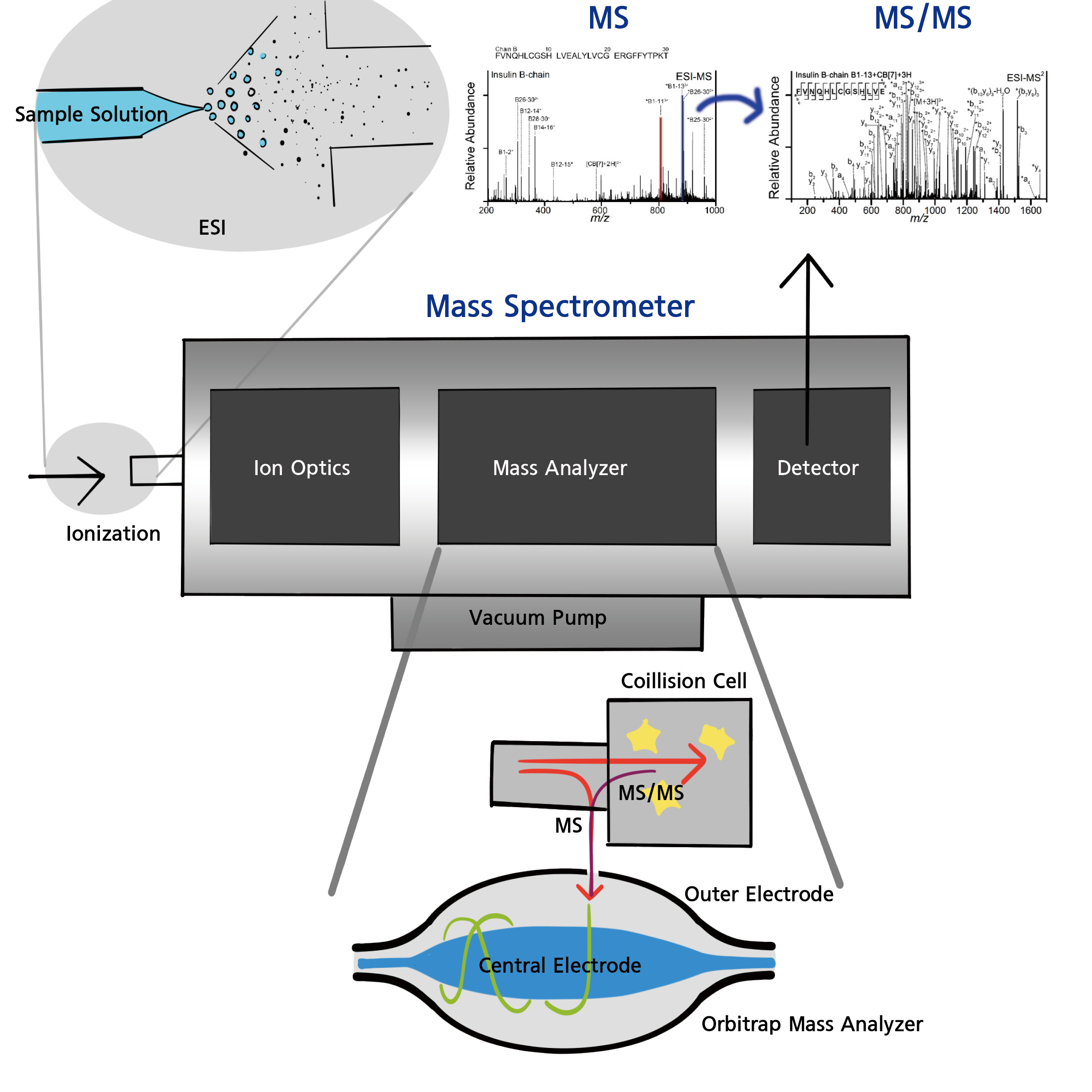

While improving the efficiency of sample preparation is important, the most critical factor in accurately analyzing small quantities of proteins with high sensitivity is the final analytical instrument. It is no exaggeration to say that all current proteomics analysis relies on mass spectrometry (MS). A mass spectrometer is an instrument that measures changes in the movement of gaseous analytes based on their mass under the influence of an electric field. To be influenced by the electric field, the analyte must be charged in the gas phase. Hence, mass spectrometry measures the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of a substance, and ionization, which gives the analyte a charge, is a crucial step.

As long as the substance can be ionized, anything from atoms and molecules to large complexes like nanoparticles can be turned into gas-phase ions and analyzed in a vacuum using electric fields. A mass spectrometer typically consists of a sample inlet, an ionization device that ionizes the analyte, a mass analyzer that separates and measures the ionized substances by m/z, and a detector that quantifies the ions.

Mass spectrometry is most actively used in proteomics and other omics fields, but also finds wide application across industries such as pharmaceuticals, petroleum, environment, and advanced materials, as well as in scientific research.

There are various ionization methods for mass spectrometry, but when coupled with LC, electrospray ionization (ESI) is the most suitable. This is because ESI can directly convert liquid-phase samples separated by LC into gas-phase ions. ESI works by applying an electric field to the tip of a capillary through which the sample flows, creating charged droplets. Molecules in the liquid become gas-phase molecular ions without being damaged—ideal for non-volatile molecules like peptides. Recently, nano-ESI is often used to maximize sensitivity.

These ionized peptide ions are separated and detected based on their m/z by analyzing how their momentum changes in the electric field. The type of mass spectrometer is determined by how this motion is induced and separated:

• If ions are accelerated in a vacuum and separated based on their flight speed, the instrument is called a Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometer (TOF-MS).

• If four rod-shaped electrodes are arranged symmetrically and the strength of the electric field is varied using radio frequencies to alter ion paths, it’s a Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer.

• If quadrupoles are arranged in all three dimensions to trap ions in orbital motion, it becomes an Ion Trap Mass Spectrometer.

• An Orbitrap Mass Spectrometer uses a barrel-shaped outer electrode and a central spindle electrode. Ions enter the trap, orbit around the spindle, and are confined. The frequency of this orbital motion, which differs according to m/z, is detected and converted into a mass spectrum.

There are many types of mass spectrometers, each with unique features. The most suitable mass spectrometer is selected depending on the nature of the analyte. For peptide analysis in proteomics, Orbitrap mass spectrometers with high sensitivity and m/z resolution are widely used.

However, simply measuring peptide ion masses is not sufficient for sequence analysis. Therefore, peptides are further fragmented within the mass spectrometer to deduce their amino acid sequences. This method is called Tandem Mass Spectrometry (MS/MS). There are various methods for fragmenting analyte ions within the mass spectrometer, and many are used depending on the molecule type. For peptide sequencing, the most commonly used method is Collision-Induced Dissociation (CID). In CID, instruments such as quadrupoles or ion traps, or a collision cell in front of the mass analyzer, apply varying electric fields using radio frequencies to increase the kinetic energy of the peptide ions. These are then collided with a gas to fragment them. The masses of the fragments are then analyzed to deduce the amino acid sequence.

Thus, mass spectrometers used in proteomics must combine high sensitivity, high resolution, and CID capability. Orbitraps integrated with ion traps or collision cells are representative examples.

The resulting data appears in the form of a spectrum that plots m/z against signal intensity. To derive meaningful information from this, the spectrum must be interpreted. However, due to the vast number of possible amino acid sequences, matching them manually is extremely time-consuming and labor-intensive. To overcome this, many protein databases and software tools have been developed.

The process begins by computationally digesting proteins from a database into peptides, and generating theoretical spectra for these peptides. These are then compared with the experimental spectra, and the most suitable peptide matches are identified. If genome information is incorporated, this becomes proteogenomics, as described in the previous post on Cancer Diseases and Proteogenomics Research. From the identified peptides, the original proteins present in the sample can be inferred.

However, due to the complexity of proteome data, false matches can occur—cases where peptides are incorrectly identified due to coincidental spectral similarity. To address this, methods like the decoy database approach are used to calculate false positive rates. A decoy database consists of reversed amino acid sequences of real proteins, used to estimate how often false matches occur. For example, if 1% of the peptides matching to protein A originate from the decoy database, the false identification rate is estimated at 1%. Research is ongoing to improve both peptide identification software and error correction techniques.

Despite advances in extraction, separation, digestion, detection technologies, and instrumentation, there are still limitations in analyzing trace amounts of proteins. Additionally, for proteins with post-translational modifications (PTMs), analyzing the exact site and degree of modification—which often correlates with disease—is still very challenging. Researchers are continuously developing new analytical methods, and companies are also pushing to improve mass spectrometers. Thanks to these ongoing improvements, high-level proteomics has become possible, and proteogenomics has emerged as a key technology in biotechnology and precision medicine.

Please visit the Hugh Kim Research Group homepage.

References

1. Zhang, Y. et al., Chem. Rev. 2013, 113 (4), 2343-2394.

2. Han, X. et al., Science 2006, 314 (5796), 109-112.

3. Tran, J. C. et al., Nature 2011, 480 (7376), 254-258.

4. Yates III, J. R., J. Mass Spectrom. 1998, 33 (1), 1-19.

5. Wu, Z. et al., Anal. Chem. 2018, 90 (16), 9700-9707.

6. Tran, B. Q. et al., J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10 (2), 800-811.

7. Wilm, M. et al., Anal. Chem. 1996, 68, 1.

8. Lane C. S. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 848-869

9. Saba, J. et al., Proteome Res. 2009, 8, 3355.

Leave a comment