Hugh Kim & Dongjoon Im

The folding of proteins and the unique structures formed through proper folding are directly linked to their functions. Misfolded proteins, however, can be associated with a variety of diseases. Protein misfolding refers to the failure of a protein to form its correct three-dimensional structure. It can occur both inside and outside cells and may result from genetic mutations, errors in protein translation, stress due to factors like heat, pH changes, oxidation, ionic strength, or incomplete complex formation. When proteins adopt incorrect structures, they are either refolded by chaperones into their correct forms or degraded by proteolytic enzymes. However, some misfolded proteins escape this removal process and form aggregates. Misfolded proteins may randomly interact with one another, potentially leading to diseases such as cancer or cardiovascular disorders.

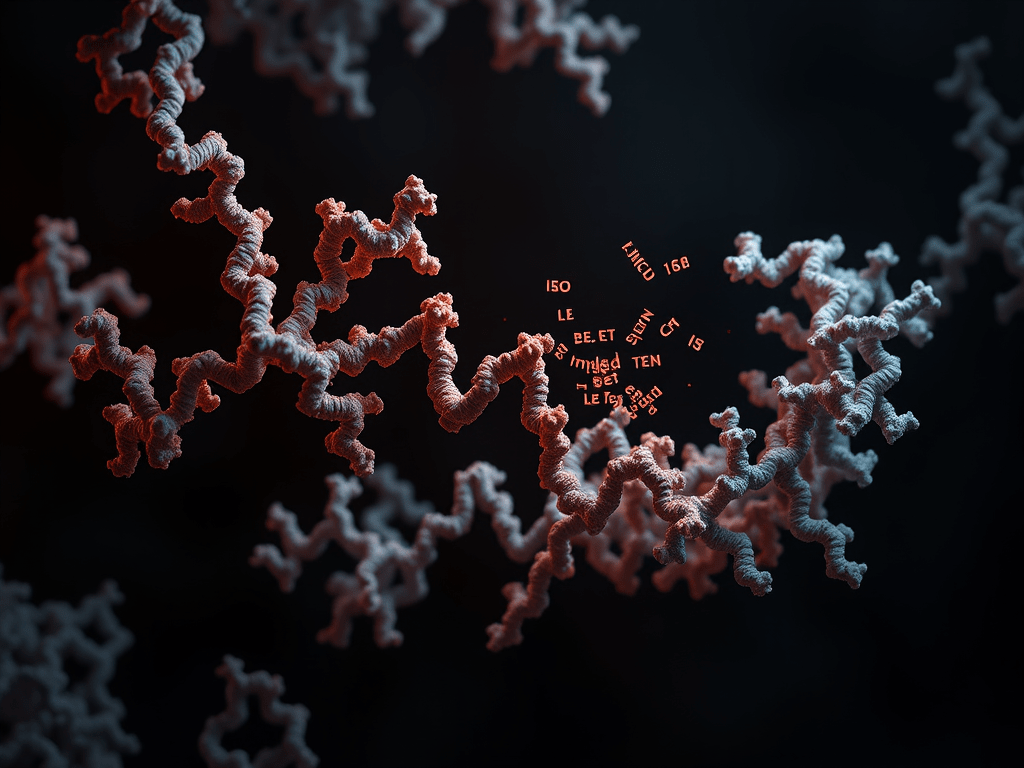

In most cases, the secondary structure that is most crucial to protein function in the properly folded state is the alpha-helix. However, when misfolded proteins begin to self-associate and aggregate, significant structural changes occur, often resulting in a beta-sheet structure where beta-strands align in a planar arrangement. While beta-sheets are also present in properly folded proteins, an increased proportion of beta-sheet structures in the overall protein conformation is characteristic of toxic aggregates called amyloid fibrils. Furthermore, as misfolded proteins transition from alpha-helices, stabilized by internal hydrogen bonds, to beta-sheet structures formed between proteins, the hydrophobic amino acid side chains become exposed to the external environment, promoting further aggregation.

Certain proteins in their misfolded states can interact with properly folded proteins, inducing misfolding and aggregation. These proteins are implicated as causes of diseases related to protein misfolding and possess a unique property: they can propagate without containing genetic material, unlike viruses. A key example is prion proteins. Prions (proteinaceous infectious particles) were first identified in 1982 as the cause of scrapie, a neurodegenerative disease in sheep and goats. Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), widely known as “mad cow disease,” is another example caused by abnormal prion protein folding. In their normal functional form, these prion proteins are denoted as PrPC (cellular prion protein), while their disease-causing misfolded counterparts are denoted as PrPSC (scrapie isoform of the prion protein). A distinctive feature of PrPSC is the dramatic increase in beta-sheet structures within its secondary structure. These exposed hydrophobic regions enable PrPSC to convert surrounding PrPC into the misfolded PrPSC form. These aggregates of beta-sheets damage neurons, causing physical and mental symptoms that eventually lead to death.

Prion proteins also uniquely influence other homologous proteins in their environment to propagate. This makes cross-species transmission of prion-related diseases challenging when prion protein sequences differ significantly between species. For instance, kuru disease, which spread among the Fore tribe in Papua New Guinea due to cannibalistic practices, had a high prevalence in that group. In contrast, variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD), linked to the consumption of BSE-infected beef, has an extremely low prevalence because of substantial differences between human and bovine prion protein sequences.

In theory, nearly all proteins could form amyloid aggregates. However, only a limited number of specific proteins show this phenomenon in practice. For amyloid aggregation to occur, proteins must first undergo structural changes, transitioning from their stable native forms to alternative conformations. This destabilization process requires proteins to overcome the stability of their native structures, a process unlikely to happen spontaneously. However, the presence of already misfolded proteins with exposed hydrophobic beta-sheet regions can create driving forces that facilitate the misfolding of nearby proteins. These interactions further promote amyloid aggregation.

The formation of amyloid aggregates involves numerous barriers, making the process time-consuming. Therefore, diseases associated with amyloid aggregates typically manifest long after aggregation begins. Once formed, amyloid aggregates, especially in the nervous system, can trigger various neurodegenerative disorders. Neurodegenerative diseases encompass conditions like Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body dementia, and Parkinson’s disease, where progressive nerve damage occurs over time. Amyloid aggregates have been found in the brains of patients with these diseases, establishing them as key markers and prompting extensive research.

For example, individuals with Down syndrome have a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease with age due to overexpression of amyloid beta protein, which is encoded on chromosome 21. While numerous hereditary neurodegenerative diseases exist, some occur sporadically without family history. As advancements in technology extend life expectancy, the prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases has grown exponentially.

Although the relationship between amyloid aggregates and some diseases remains partially unclear, clinical observations over extended periods strongly suggest causative links. Understanding the formation and causes of amyloid aggregates driven by protein misfolding and intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) is crucial for advancing treatments for neurodegenerative diseases. Consequently, efforts to inhibit amyloid formation are essential in combating these conditions.

Please visit the Hugh Kim Research Group homepage.

References

- Lin, M. T., & Beal, M. F. Nature 2006, 443 (7113), 787-795

- Dobson, C. M. Nature 2003, 426 (6968), 884-890

- Prusiner, S. B. Science 1982, 216 (4542), 136-144

- Collinge, J., et al. Nature 1996, 383 (6602), 685-690; Hill, A. F., et al. Nature 1997, 389 (6650), 448-450; Bruce, M. E., et al. Nature 1997, 389 (6650), 498-501

- Sugase, K., et al. Nature 2007, 447 (7147), 1021-1025

- Patterson, C. World Alzheimer report 2018, 2018

- Glenner, G. G., & Caine W. W. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1984, 120 (3), 885-890; Spillantini, M. G., et al. Nature 1997, 388 (6645), 839-840

- Masters, C. L., et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1985, 82 (12), 4245-4249

- Mullan, M., et al. Nat Genet 1992, 1 (5), 345-347

Leave a reply to Pathogenic Proteins, Diseases, and Treatment – Leo & Leah Cancel reply