Hugh Kim & Soo Yeon Chae

When we talk about studying proteins, most people immediately think of “meat.” Among the three major macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—carbohydrates and fats are highly similar to the molecules we consume and those that function within our bodies. Because they are readily absorbed and utilized, they are often processed to be more appealing to our taste buds. However, proteins are still commonly consumed through “meat.” As mentioned in the previous post, our body’s cells can be likened to cities where proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates interact, with proteins playing a role similar to the inhabitants of the city. Proteins are the most crucial components of cells, facilitating transport, catalysis, and signal transmission to maintain life processes. Additionally, proteins form structures such as muscle fibers, tendons, and connective tissues. The basic units of proteins, amino acids, can be synthesized within our bodies, but they are primarily obtained by consuming and digesting protein-rich foods. We consume animal muscles, tendons, and connective tissues as a source of protein. Animal muscle comprises approximately 75% water, 20% protein, and 5% fat and carbohydrates. The protein portion mainly consists of actin and myosin filaments arranged in muscle fiber bundles. This means that the proteins we consume as food differ slightly from the proteins studied in proteomics for understanding life phenomena.

Proteomics research focuses on proteins found in biological tissues or blood. While proteins in our bodies can be derived from “meat” we consumed, the scope of proteomics extends far beyond that. Proteomics research primarily targets specific biological phenomena or diseases. When combined with genome-wide analysis, this field becomes known as proteogenomics. Proteogenomics involves generating extensive genomic and proteomic data from biological samples, integrating these datasets to gain deeper insights into life processes and diseases, and ultimately applying these findings to improve disease diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and personalized treatment. In particular, proteogenomics is a key technology in next-generation precision medicine, which focuses on “prevention and treatment tailored to individual patient differences.” The most promising and actively studied application of proteogenomics is cancer research. Despite advances in modern medicine, as of 2020, approximately 60 – 80 million people worldwide were still battling cancer, making it the second leading cause of death globally. Cancer remains one of the greatest challenges in biomedical science.

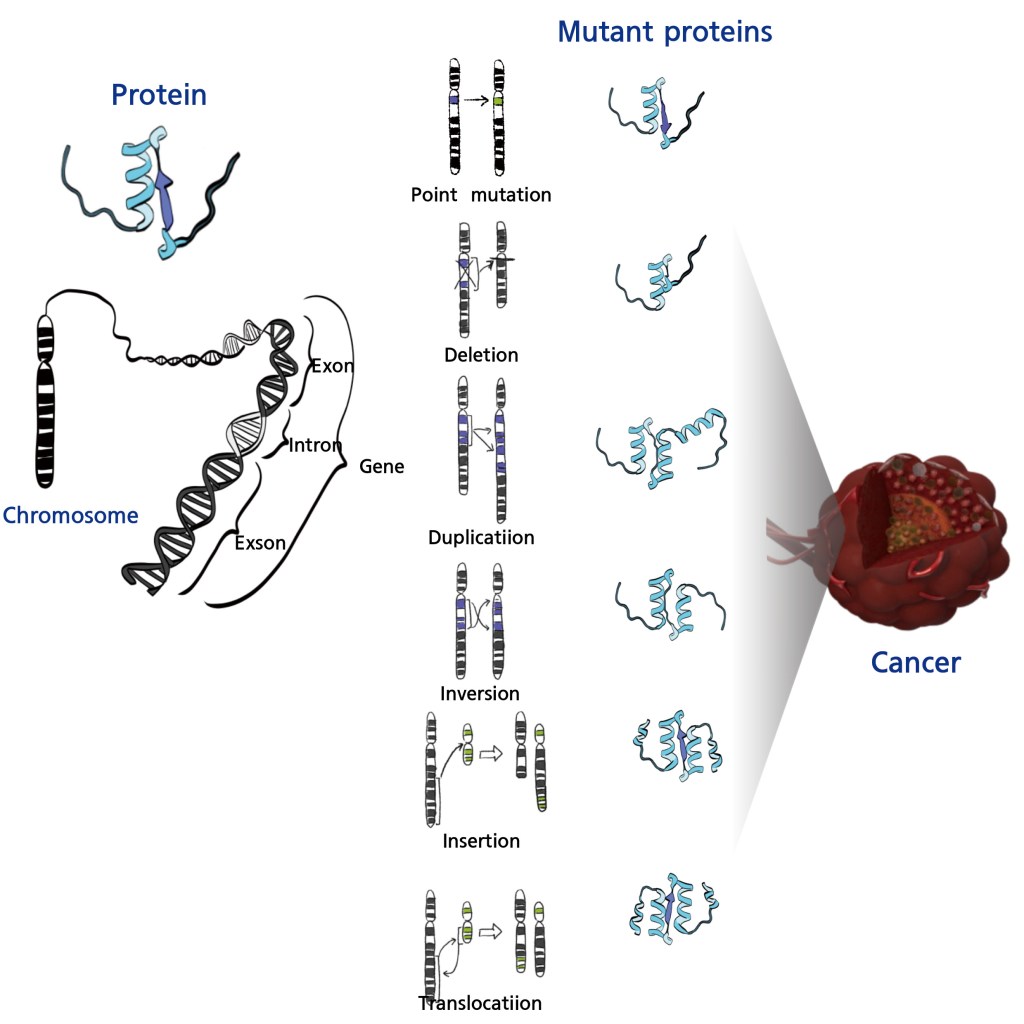

The suffix “-omics” used in terms like genomics and proteomics refers to the study of entire sets of molecules within a biological system. It comes from the Greek root “-ome” (meaning “whole”) and the scientific suffix “-ics” (denoting a field of study). This concept extends across multiple disciplines, including genomics (the study of all genes in an organism), proteomics (the study of all proteins), metabolomics (the study of metabolites), and glycomics (the study of glycans). Among these, genomics plays a crucial role in cancer research because it provides a “blueprint” of diseases. In cancer diagnosis, genomic analysis helps assess tumor characteristics and predict prognosis. Genomic testing involves sequencing chromosomal DNA within cell nuclei. Unlike normal cells, cancer cells exhibit chromosomal abnormalities known as mutations, which include deletions (loss of chromosome segments), duplications (extra copies of segments), inversions (reversed segments), and translocations (segments relocating to different chromosomes). In some cases, mutations may not impact cell function, as they do not alter protein structure or function. However, many chromosomal changes do affect protein characteristics, thereby influencing cellular physiology and leading to diseases such as cancer.

If genomic alterations are the root cause of cancer, then proteins reflect the disease’s characteristics. Proteins, as the functional molecules of cells, provide crucial insights into cancer cell behavior. A hallmark of cancer cells—uncontrolled and rapid growth—can be linked to the overexpression of proteins involved in cell proliferation and regulation. Normally, immune cells should detect and destroy abnormally growing cells. However, cancer cells evade immune detection by overexpressing various cancer-testis (CT) antigens that help them escape tumor-specific immune responses. Additionally, cancer cells may alter protein-protein interactions and signaling pathways to resist chemotherapy or other drug treatments. Thus, while genomics provides a disease blueprint, proteomics reveals the current state and progression of the disease. Proteomic research offers crucial information for cancer diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and personalized treatment strategies.

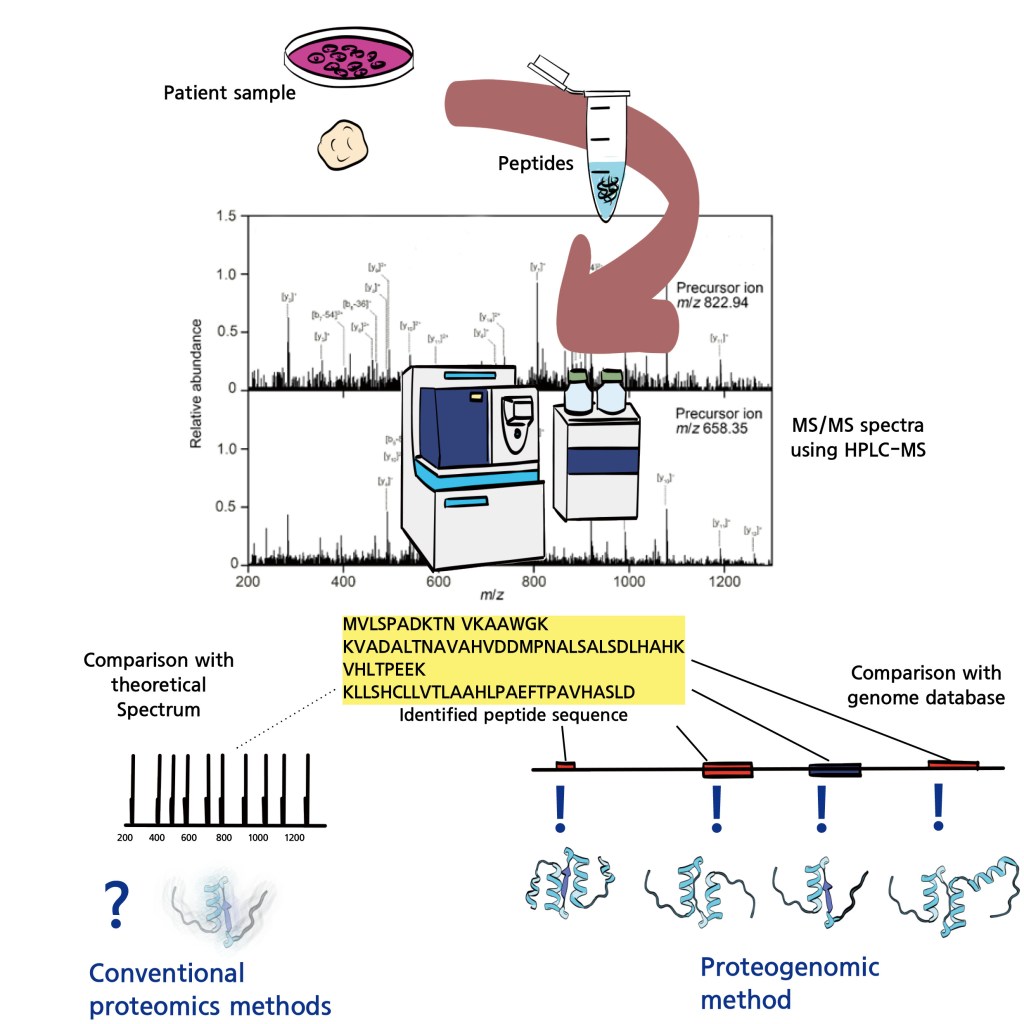

Genomics and proteomics have historically been studied independently in the context of cancer and other diseases. However, proteogenomics emerged in 2004 as an integrated approach, and since 2016, it has become a crucial field for cancer research. The core methodology of proteomics involves extracting proteins from cells, digesting them into peptides using enzymes, and analyzing them using liquid chromatography (LC) and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). A key step in proteomics is identifying peptides from MS/MS spectra and reconstructing the complete proteome. Typically, this is done by comparing experimental MS/MS spectra with a pre-existing theoretical proteome database. However, a major limitation is that novel mutations, such as mutant peptides linked to cancer, may not be present in reference databases, making them difficult to detect.

To overcome this limitation, researchers utilize genomic analysis-based peptide sequence databases to identify novel peptides. In other words, genome data is integrated into proteomic analysis, which is the essence of proteogenomics. Initially, proteogenomics focused on comparing genomic and proteomic data to assess gene expression and protein translation. However, its scope has since expanded to real-time monitoring of molecular changes in actual patient cells through integrated genome and proteome analyses. This revolutionary approach has established genoproteomics as a core technology in next-generation precision medicine.

Please visit the Hugh Kim Research Group homepage.

References

1. Nesvizhskii, A. I., Nat. Methods 2014, 11 (11), 1114-1125.

2. Zhou, Y. et al., J. Hematol. Oncol. 2020, 13 (1), 170.

3. Mani, D. R. et al., Nat. Rev. Cancer 2022, 22 (5), 298-313.

4. Menschaert, G., Fenyö, D., Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2017, 36 (5), 584-599.

5. Chae, S. Y., Nam, D., Hyeon, D. Y., Hong, A. et al., iScience 2021, 24, 102325

6. Verma, S., Gazara, R. K., Chapter 3 – Next-generation sequencing: an expedition from workstation to clinical applications. In Translational Bioinformatics in Healthcare and Medicine, Raza, K.; Dey, N., Eds. Academic Press: 2021; Vol. 13, pp 29-47.

Leave a comment