Hugh Kim & Soo Yeon Chae

Understanding biological phenomena and overcoming diseases require research at the molecular level. A molecule is the smallest functional unit formed through atomic chemical bonding. While some substances, such as metals, exhibit unique properties at the atomic level, most materials derive their distinct functions at the molecular level. The three essential macronutrients—carbohydrates, proteins, and fats—also exhibit characteristics that originate at the molecular level. All of these are organic compounds primarily composed of carbon (C). Hydrocarbons, which consist of carbon and hydrogen (H), serve as the foundation of these molecules, with additional elements such as phosphorus (P), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and sulfur (S) forming polar functional groups. The specific bonding and arrangement of these elements determine the characteristics of the molecules, which in turn classify them as carbohydrates, proteins, or fats.

Most of the macronutrients we consume exist in food as macromolecules or complexes. Through the process of digestion, they are broken down into their molecular components, absorbed, and utilized according to their respective functions in the body. Chemical reactions play a crucial role in this process, making the human body comparable to a biochemical research laboratory where complex chemical reactions continuously occur.

In universities and research institutions, departments are usually organized based on the subject of study. Within these departments, research laboratories are further specialized according to specific research topics, with researchers conducting experiments and investigations. Similarly, in the human body, tissues function as departments, and cells operate as laboratories. Within these cellular laboratories, proteins—one of the three macronutrients—act as the “researchers” conducting biochemical reactions.

In other posts on this blog under the theme “What We Eat and Drink,” cells were metaphorically described as water-immersed cities, where proteins interact with lipids and carbohydrates, acting as the inhabitants. In this analogy, proteins drive and regulate bodily functions through their interactions.

Proteins are formed through chemical reactions known as peptide bonds, which link amino acid molecules. Remarkably, only 20 types of amino acids are used to build proteins, yet their diverse combinations give rise to a vast array of proteins in the body. Proteins can range in size from small peptides composed of about ten amino acids to massive proteins consisting of tens of thousands of amino acids. The 20 amino acids combine in various ways to fulfill distinct functions, leading to the formation of a wide variety of proteins in the human body.

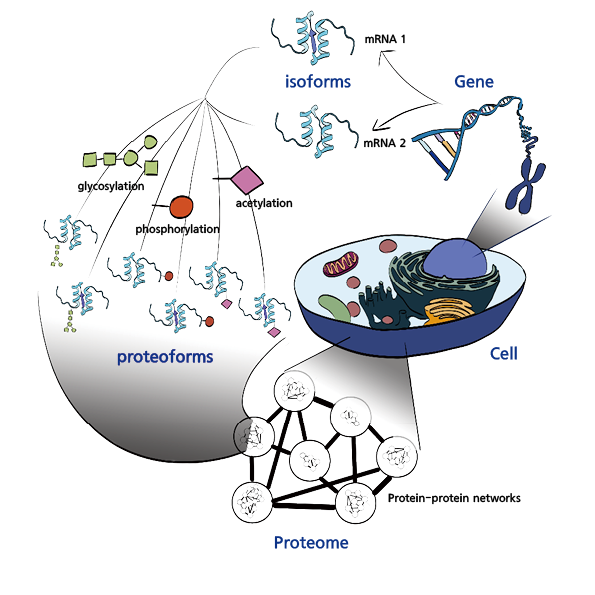

However, the exact number of protein types present in the human body remains unknown. Genetic analysis, which deciphers the nucleotide sequences encoding proteins, suggests that there are at least 20,000 different proteins. However, variations in the length of proteins during gene expression imply that the total number could range from hundreds of thousands to even a million different proteins. This hypothesis is based on the concept of RNA splicing, a process during which messenger RNA (mRNA) is transcribed from DNA and undergoes modifications that generate different mRNA variants. Consequently, a single gene can produce multiple protein products, altering biological functions and generating new protein functionalities.

This theory emerged during the Human Genome Project, which began in 1990 and concluded in 2003. The project revealed that humans have far fewer genes than previously expected, prompting the search for alternative explanations for our biological complexity. However, over the past two decades of proteome research, many of the proteins predicted to arise from extensive RNA splicing have not been detected, leading to debates about whether the number of distinct proteins in the human body is significantly lower than originally estimated.

The complexity of proteins is most evident in post-translational modifications (PTMs), which refer to chemical changes that occur after proteins are synthesized. There are approximately 400 known types of PTMs, and each protein can undergo multiple modifications, dramatically increasing the diversity of protein structures and functions. The extent of PTMs remains a subject of debate, with phosphorylation—one of the most common PTMs—affecting anywhere from 10% to as much as 80% of proteins in the body. While estimates vary, PTMs undeniably contribute to the vast diversity of proteins.

Understanding the structure and function of individual proteins is critical for deciphering biological processes and advancing medical research, particularly in drug development. However, to fully comprehend cellular phenomena and protein functions, it is not enough to study individual proteins in isolation. Just as a single person performs multiple roles in society—such as being a spouse and parent at home, a professor at a university, and a scientist in the broader community—proteins also serve multiple functions and interact with various other proteins. Studying a single protein in isolation does not provide a complete understanding of its role within the cell.

For this reason, researchers study the entire proteome—the complete set of proteins within a cell—giving rise to the field of proteomics.

The significance of proteomics continues to grow as medical technology advances, particularly in areas such as drug development and personalized medicine tailored to individual patients. However, as previously mentioned, the complex interplay of variations from DNA to RNA, along with PTMs, exponentially increases the complexity of the human proteome, posing significant challenges for proteomics research.

Please visit the Hugh Kim Research Group homepage.

References

1. Omenn, G. S. et al. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15 (11), 3951-3960.

2. Paik, Y.-K. et al. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15 (11), 3945-3950.

3. Tress, M. L. et al. PNAS 2007, 104 (13), 5495-5500.

4. Tress, M. L. et al. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42 (2), 98-110.

5. Aebersold, R. et al. Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14 (3), 206-214.

6. Sharma, K. et al. Cell Rep. 2014, 8 (5), 1583-1594.

7. “Protein Phosphorylation” Kinexus Bioinformatics Corporation. http://www.kinexus.ca/scienceTechnology/phosphorylation/phosphorylation.html

Leave a comment