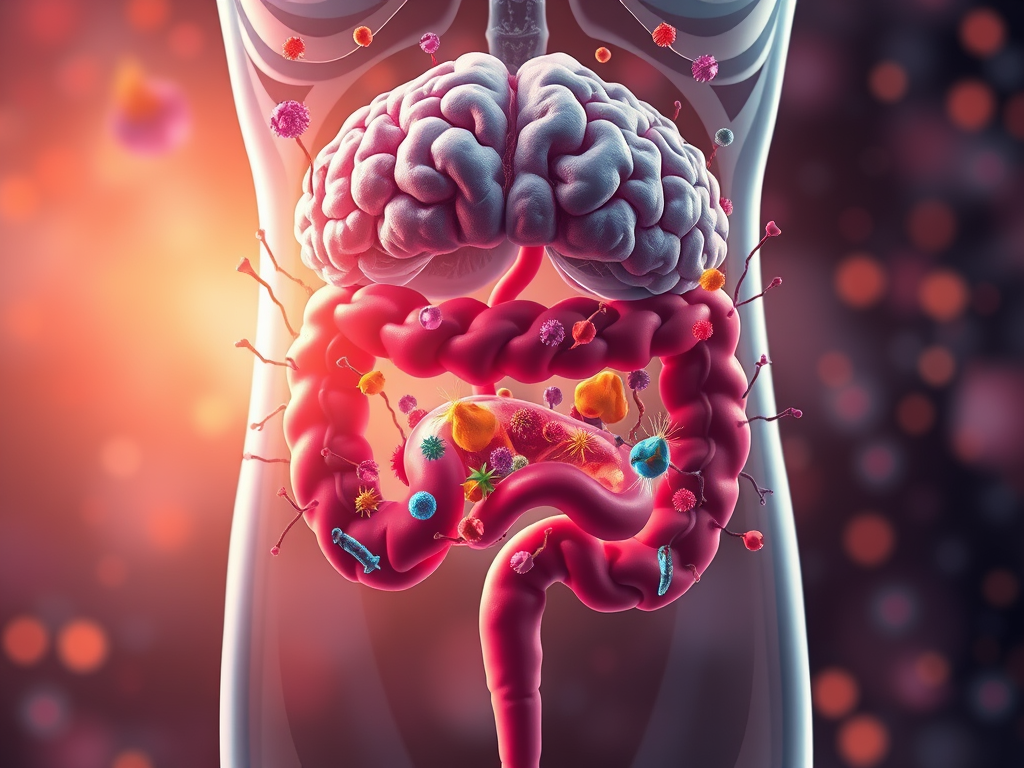

I am conducting research at the molecular level to identify the pathogenesis of specific diseases and develop treatment strategies. My primary research areas include cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Recently, the academic community studying neurodegenerative diseases has been paying increasing attention to the impact of gut microbiota and gut health on these conditions. In particular, through the concept of the gut-brain axis, it has been revealed that gut microbiota significantly influence brain health. The gut is the organ with the highest concentration of nerve cells after the brain, which supports the idea that gut health is closely linked to the nervous system. The gut and brain interact through the nervous, immune, and endocrine systems, with gut microbiota playing a crucial regulatory role in these connections. In other words, the gut microbiome is essential for overall health, and an imbalance can be associated with the development of degenerative neurological diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, as well as inflammatory diseases, immune disorders, and cancer.

The gut hosts a diverse range of microorganisms. As omnivores, humans have intestines that are longer than those of carnivores but shorter than those of herbivores. Carnivores have relatively short intestines because they need to rapidly digest and expel proteins and fats, which are prone to putrefaction. They also secrete strong stomach acid (pH 1–2) to break down meat quickly. Their gut microbiota mainly consist of microbes specialized in protein and fat digestion, with little fermentation occurring, resulting in lower microbial diversity. In contrast, herbivores have relatively long intestines to absorb nutrients from fiber-rich plants. Their gut microbiota engage in fermentation to break down fibers, allowing for energy absorption, but the process takes significantly more time.

As omnivores, humans possess a complex gut microbiome that reflects characteristics of both carnivorous and herbivorous animals. Proteobacteria are a part of the gut microbiota and are present in small amounts in a healthy human gut. Pathogenic bacteria such as Escherichia coli (E. coli), Salmonella, and Helicobacter pylori belong to this group. Normally, Proteobacteria remain at low levels in a healthy gut. However, their dominance in the gut is associated with gut microbiota imbalance (dysbiosis), which is considered a negative health indicator. Meanwhile, beneficial bacteria, such as lactic acid bacteria, mainly metabolize fiber, acidify the gut environment, and inhibit the growth of pathogenic bacteria. The composition of the gut microbiota is influenced by dietary habits, highlighting the importance of a healthy diet.

Although maintaining a gut environment dominated by beneficial bacteria is crucial, it is unfortunately difficult to fundamentally alter the gut microbiota composition after reaching adulthood. Most of the gut microbiota composition is determined within the first 1–3 years of life, making it challenging to significantly change it later in life. The initial formation and composition of the gut microbiome are influenced by mode of birth, early nutrition, and upbringing environment. However, even after this early stage, gut microbiota composition is not entirely fixed; it can be affected by environmental factors, diet, lifestyle, medication use, and stress. While the gut microbiota tends to maintain a relatively stable structure in adulthood, it can undergo structural changes in response to drastic environmental shifts or sustained stimuli.

A prime example of negative changes in gut microbiota occurs due to a diet high in fat, sugar, and processed foods, as well as habitual alcohol consumption. These dietary habits can increase the proportion of harmful bacteria while reducing beneficial bacteria. A decrease in microbial diversity can destabilize the gut ecosystem, leading to increased inflammation, a higher risk of metabolic diseases (such as obesity and diabetes), and weakened intestinal barriers. This weakening can result in leaky gut syndrome, where toxins and microbial metabolites enter the bloodstream, triggering inflammatory responses.

Additionally, prolonged use of antibiotics and other medications can negatively impact gut microbiota composition. Many harmful bacteria have genetically developed antibiotic resistance to survive exposure to these drugs. As a result, long-term antibiotic use can lead to an overgrowth of antibiotic-resistant harmful bacteria in the gut while reducing beneficial bacteria that normally compete with them, thereby increasing the risk of various diseases. To prevent and manage these bacterial infections, antibiotics should be used judiciously, and maintaining gut microbiota balance should be a priority.

Maintaining a healthy gut microbiome requires consistent effort even in adulthood. One example is probiotic consumption. However, simply consuming probiotics does not instantly shift the gut microbiota toward a beneficial state. The newly ingested probiotics struggle to displace the already established core microbiota and form stable colonies, as the existing microbiota have already occupied available ecological niches. Additionally, probiotics consumed orally face survival challenges as they pass through strong stomach acid and bile before reaching the intestines. Even if a certain amount of probiotics successfully reaches the intestines, they must interact with the intestinal mucosa and compete with existing microbes to establish themselves. Since probiotics generally have lower competitive survival ability compared to resident gut bacteria, their long-term colonization is difficult.

As a result, probiotic intake can cause temporary changes in gut microbiota, but once consumption stops, the gut often returns to its original state. Studies have shown that probiotics can be detected in stool while they are actively consumed, but most are eliminated once intake ceases. This indicates that probiotics primarily act as “passengers” rather than “residents” in the gut. Due to this, infrequent or sporadic probiotic intake is unlikely to have a significant effect. Instead, regular and continuous probiotic intake is necessary to expect any beneficial effects. Moreover, consuming probiotics alone is not enough; dietary fiber, which serves as food for beneficial bacteria, is equally important. Ensuring sufficient intake of viable probiotics in the right amounts is also crucial.

In the next post, I will discuss how to choose the right probiotics, how to consume them, and what additional efforts can be made to maintain gut health.

Summary

Gut-Brain Connection: The gut microbiota significantly influences brain health through the gut-brain axis.

Gut Microbiota & Health: Imbalances are linked to neurodegenerative diseases, inflammation, immune disorders, and cancer.

Human Gut Microbiota: Reflects both carnivorous and herbivorous traits; Proteobacteria can indicate dysbiosis.

Diet & Microbiota: Poor diet (high in fat, sugar, and processed foods) and excessive antibiotics or alcohol disrupt gut balance.

Probiotics: Provide temporary effects; regular intake is necessary for sustained benefits.

Key to Gut Health: A balanced diet rich in dietary fiber supports beneficial gut bacteria.

Next Topic: How to choose and consume probiotics effectively.

References

- Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy volume 9, Article number: 37 (2024)

- Scientific Reports volume 14, Article number: 15460 (2024)

- Case Adams, Probiotics Simplified How Nature’s Tiny Warriors Keep Us Healthy, 2014, Logical Books

Leave a comment