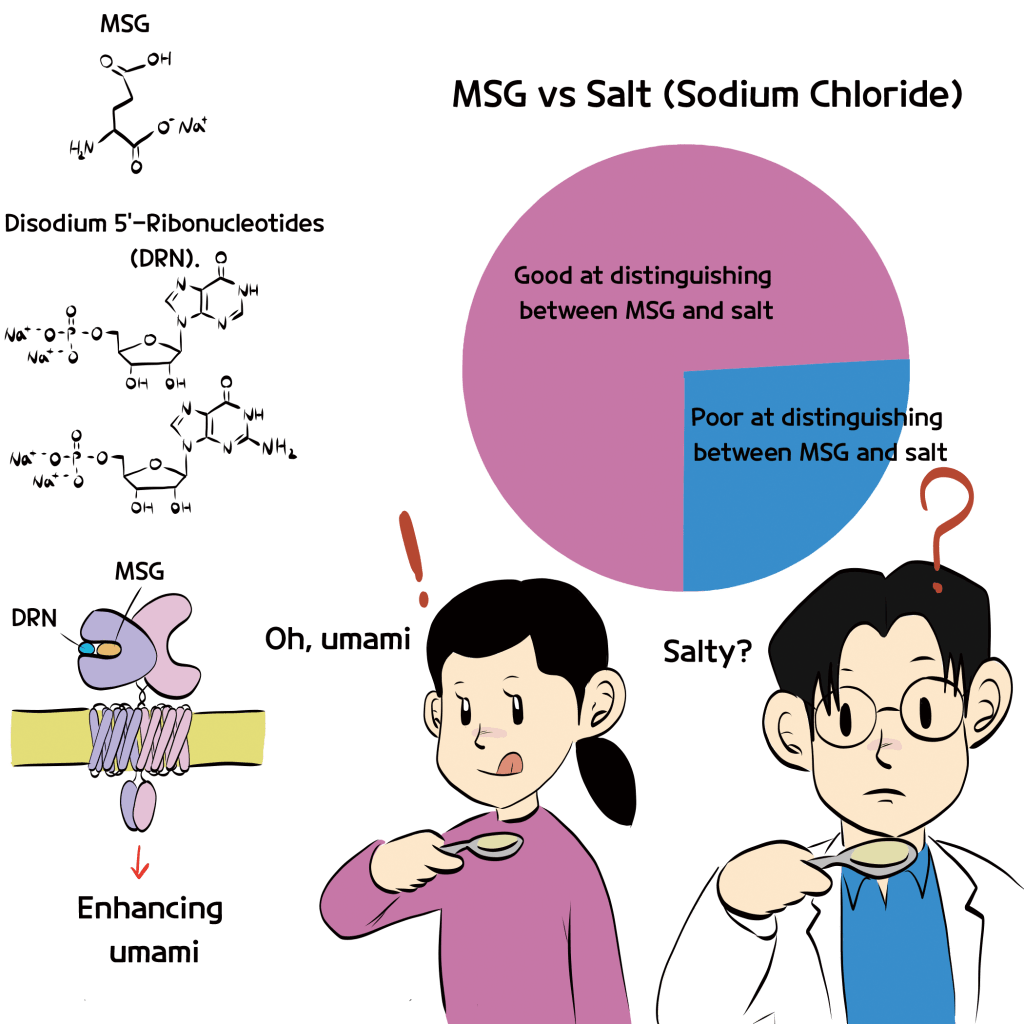

Monosodium glutamate (MSG) provides umami flavor through complex chemical interactions. If you taste glutamic acid without sodium ions, it would present a sour flavor, characteristic of acidic molecules. The umami flavor of MSG and the salty taste of sodium chloride can be distinguishable or not, depending on the individual. In a 2002 experiment, many people were able to differentiate between MSG and NaCl, but around 27% of participants could not tell the difference between the two at lower concentrations. Those who had difficulty sensing umami often confused it with saltiness, suggesting they may be more sensitive to the salty taste of sodium ions than the umami taste of glutamate ions. There are also reports that umami can enhance the perception of saltiness, indicating some correlation between the recognition of salty and umami flavors.

Recently, MSG has been recommended as a substitute to address excessive sodium chloride (salt) intake. The sodium ion content in MSG is 12.28 g per 100 g, which is about one-third of the sodium content in NaCl (39.34 g/100 g). According to recent reports, replacing some of the salt in food with MSG can reduce sodium ion intake by 25 – 40%. However, some people may experience complex symptoms related to MSG consumption, and MSG has been negatively perceived by the public for decades, so whether it will be accepted as a salt substitute in regular households remains uncertain.

MSG’s umami taste can be enhanced by molecules known as Disodium 5′-Ribonucleotides (DRN). Since ribonucleotides are components of RNA, they are also present in many of the foods we eat, similar to MSG. These ribonucleotides cannot activate umami receptors (T1R1/T1R3) on their own, but when combined with glutamate ions, they can bind to the receptors and amplify the umami sensation.

You may have seen processed foods emphasize that they no longer add MSG, due to the misconception that MSG is harmful. I’ve noticed that MSG is no longer listed among the ingredients of products like instant ramen. I’m unsure whether this means that MSG is included or not. However, if you look closely, you might spot ingredients like ‘5’-ribonucleotides,’ which work in conjunction with MSG. This suggests that, in some form, MSG is still present in the product. I recall a TV show mentioning that ramen soup bases use natural seasonings like soy sauce, amino acid powders, or kelp and mushroom extracts to create umami flavor, instead of adding MSG. However, these natural seasonings inherently contain MSG. So why are companies playing this game of hide-and-seek? Besides the MSG symptom complex, people also believe MSG is harmful simply because it is a synthetic additive. In reality, MSG is not synthesized in a lab but produced through the fermentation of sugar extracted from sugarcane, though chemical separation methods are used in the process.

Molecules isolated from naturally occurring substances, with unnecessary components or impurities removed, are not inherently worse in terms of safety or dosage. One of the best examples of this is pharmaceuticals. For example, acetaminophen (a common brand name is Tylenol), a frequently used painkiller, is much more expensive in pharmaceutical grade than its 99% pure form. In theory, we could take a much cheaper version of Tylenol, but we don’t. This price difference stems from pharmaceutical quality control/quality assurance (QC/QA) processes, which ensure the drug is free of impurities, preventing any unnecessary or unknown substances from being ingested. Isolating compounds to achieve purity is fundamental to chemistry, yet it remains a challenging process. Similarly, isolating specific ingredients like MSG incurs additional costs compared to not isolating them. Ultimately, it is better to know exactly what you are consuming in terms of both identity and quantity, rather than ingesting a mixture of unknown substances.

One of my most memorable childhood experiences with MSG was with “flavored salt” in Seoul, Korea. During elementary school, I visited a street food stall with a friend and tried Korean blood sausage (sundae) for the first time. I hesitated at first because I wasn’t sure what it was, but after dipping a piece into a mixture of sesame seeds, salt, and MSG, the taste left a lasting impression. When I returned to Korea from the U.S. in 2010, I found it interesting to see blood sausage served with a soybean paste (doenjang) sauce in the southeastern region of Korea. The way blood sausage is eaten varies by region, but if you think about it, whether it’s flavored salt, soybean paste, or soy sauce, the key taste elements are similar—sodium chloride and MSG. The key difference lies in whether MSG is added directly to salt or naturally formed through the fermentation of soybeans in saltwater. When considering the idea of using MSG as a salt substitute, it’s worth noting that MSG is already mixed with salt in countries like Korea, Japan, China, and even the USA (such as in soy sauce). I believe the real issue is not public misunderstanding of MSG, but whether people are ready to view these two components separately.

References

- Kurihara, Biomed Res Int. 2015, 2015, 189402

- Pepino et al. Obesity, 2010, 18, 959–965

- Yamaguchi, S., & Kimizuka, A. (1979). Glutamic acid: Advances in biochemistry and physiology, New York: Raven Press

- Wallace et al. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2691

- Maluly et al. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 5, 1039–1048

- Pomranz, Replacing Table Salt with MSG Could Help Reduce Your Sodium Intake, Study Says, Food&Wine, November 11, 2019

- Mouritsen & Khandelia, FEBS J. 2012, 279, 3112-3120

Leave a comment