Water is an exceptionally unique molecule. It consists of two hydrogen atoms bonded to a single oxygen atom. The oxygen atom, which has an affinity for electrons, exhibits a partial negative charge, while the two hydrogen atoms possess partial positive charges. Although it is a small molecule with a molecular weight of only 18 Da (using the atomic weight of carbon, which is 12 Da, as a reference), water exists as a liquid at our everyday atmospheric pressure and temperature (i.e., 1 atm and room temperature).

Among the commonly known liquids, water is the most polar. The interaction between atoms in a molecule due to electrostatic forces arising from the abundant electrons of the hydrogen atoms and the adjacent oxygen atom is called “hydrogen bonding.” Water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen atoms rich in electrons, allowing water molecules to form hydrogen bonds with one another. Due to the polarity of water molecules and the electrostatic forces between them, some water molecules within bulk water disassociate into hydrogen ions (H+) and hydroxide ions (OH–). Typically, in a liquid state, water exhibits a concentration of 10-7 moles per liter (M) for water molecules disassociating and yielding an equal amount of hydrogen ions and hydroxide ions. This results in a pH of 7 for water, which is considered neutral. As the concentration of hydrogen ions in water increases, it is referred to as an acidic solution, and the pH decreases.

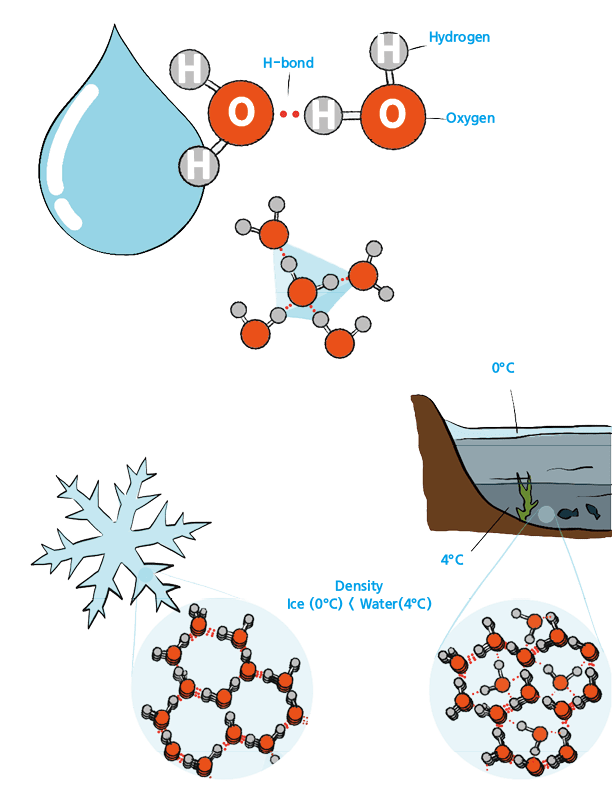

Water molecules are relatively small and lack flexibility. Despite their lightness and strong polarity, water molecules form strong hydrogen bonds with each other. However, due to their lack of flexibility, these hydrogen bonds must be aligned in a specific direction to be maintained. Water molecules form hydrogen bonds with four other water molecules around them in a tetrahedral arrangement. When water is in its liquid state, the molecules are in constant motion, breaking and forming hydrogen bonds, which allows for easy movement.

When the temperature drops below 0°C (32°F), the movement of water molecules ceases, and it transitions into a solid state known as “ice.” During this phase change, water molecules form hydrogen bonds in a tetrahedral arrangement, causing them to solidify in a hexagonal structure. As a result, ice crystals have a pointed, hexagonal structure, which is why snowflakes and ice crystals have such distinct shapes. Because of the hexagonal crystal structure, ice occupies more volume than liquid water, making it less dense. This is why ice floats on water.

At 4°C (39.2°F) and under normal atmospheric pressure, water reaches its maximum density. At lower temperatures, the slowed movement of water molecules allows them to arrange in a hexagonal structure. However, the water molecules that can still move fill the spaces between the hexagonal structures, increasing the density. This phenomenon is why, during winter, the temperature at the bottom of lakes or ponds remains at the highest-density point of 4°C, preventing the water from freezing completely and allowing fish to survive.

The boiling point of water is 100°C (212°F) at atmospheric pressure. This is a very high temperature. Water transitions from a liquid to a gas at this high temperature due to strong hydrogen bonding. A significant amount of heat is required to break the strong interactions between water molecules and transition them into a gaseous state. Boiling water at high temperatures has long been used for the purpose of disinfection, effectively killing bacteria. Like other living organisms, bacteria consist of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. Proteins in water undergo structural changes at temperatures between 60°C and 70°C, as heat disrupts the normal protein structure. Water can reach high temperatures up to 100°C in its liquid state, making it possible to use boiling water to denature the proteins inside bacteria, thus ensuring disinfection. Water, which makes up over 60% of our bodies and requires a daily intake of 2 liters, is truly a remarkable substance and a source of life.

References

1. Lucy and Harris, (2017) Quantitative Chemical Analysis. 9th Ed., W.H. Freeman and Co.

2. Oxtoby et al. (2002) Principles of modern chemistry. Thomson/Brooks/Cole

3. World Health Organization. Sustainable Development and Healthy Environments Cluster. (2005). Nutrients in drinking water. World Health Organization.

4. Sengupta, Int. J. Prev. Med., 2013, 8, 866

Leave a comment