When you walk into a convenience store, you’ll encounter a multitude of beverages filling up an entire section of the refrigerated display. Even when you open your home refrigerator, you’ll find it packed with various drinks, including water, juice, coffee, tea, soft drinks, sports drinks, and milk. You can see that a wide range of beverages, all based on water, are produced and continuously consumed. I spend all weekend wrestling with my eight-year-old daughter because of these beverages. I bet it’s a familiar scene in any household – a child wanting to drink various advertised beverages from TV and a parent simply saying, “Drink water.”

One of the topics I learned about as an elementary student was the potential harm of “cola” soft drinks. Yet, even as I’ve reached my mid-40s, the beverage I most frequently consume, after water, is still cola. My wife has always criticized my love for cola. She scolds me every time I drink it, saying, “Why do you keep drinking something that’s not good for your health?” Let’s look closer at the world’s most widely sold dark liquid, cola.

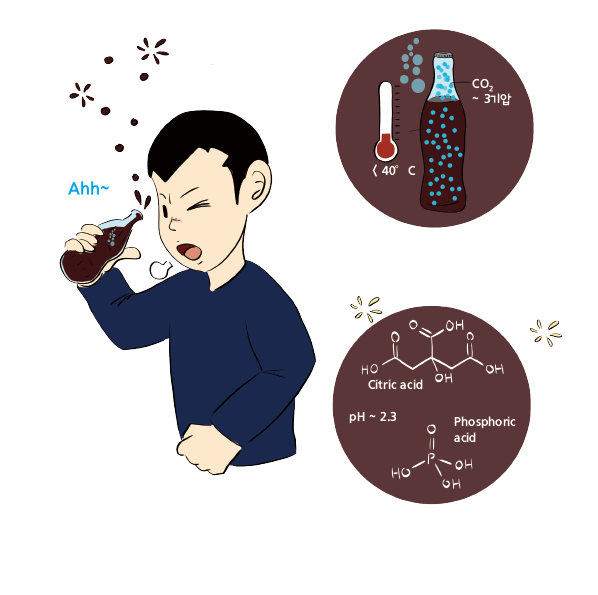

Cola is a carbonated soft drink that typically includes food additives. In the 18th century, carbonated water was created by injecting carbon dioxide into water under high pressure, and it quickly became a popular form of bottled water throughout Europe. Carbonated water is primarily made by injecting carbon dioxide (CO2) into cold water. CO2 dissolves in water at very low concentrations. By increasing the gas pressure and lowering the water’s temperature, the solubility of CO2 can be enhanced. Typically, carbonated water is created by injecting CO2 into water with a temperature below 40°F under high pressure. To maintain the concentration of CO2 in carbonated water, it is sealed in a container with a pressure of 2.5 – 3.5 atm (36.7 – 51.4 psi). When you first open a soft drink bottle, the high-pressure carbon dioxide inside the bottle rushes out quickly. Even if you reseal it, the reduced partial pressure of CO2 will lead to a drop in the concentration of CO2 inside the soft drink, causing it to become flat.

In the United States, the CO2 emissions from soft drinks and carbonated water are reported to account for only 0.001% of the total CO2 emissions in the country. Most of the CO2 used to produce carbonated beverages comes from by-products of ethanol production. Ethanol production volumes influence the supply of CO2. As a result, in 2018 and 2020, difficulties were encountered in producing carbonated beverages due to rising natural gas prices and the COVID-19 pandemic.

The primary ingredient in carbonated beverages, including cola, is carbonated water. This component, which is essentially water infused with CO2, is generally not considered to have a significant impact on our bodies other than causing us to burp as we release CO2. Carbonated water typically has a pH of around 4 – 6, making it slightly acidic, but it is still higher in pH than the stomach’s acidic environment. While it can provide mild stimulation to the stomach, it is unlikely to cause digestive disorders if consumed excessively over an extended period.

The refreshing taste of cola comes from the weak acid substances added to it. In addition to CO2, cola contains citric acid and phosphoric acid, giving it a relatively low pH of around 2.3 to 2.5. Citric acid is a weak acid commonly found in citrus fruits. Known for its distinctive tart flavor, it is used as an additive in various beverages. It is also a substance produced in the body’s energy metabolism (TCA cycle) in organisms that respire with oxygen. Since it is a substance produced in the body, it is not highly toxic but more acidic than vitamin C (ascorbic acid) or acetic acid (vinegar).

Phosphoric acid, which is more acidic than citric acid, is added to create a tangy taste. Phosphoric acid is a component of ATP, DNA, RNA, cell membranes, bones, and teeth. It is essential for all living organisms, too. Specifically, phosphoric acid combines with calcium ions to form calcium phosphate, a major component of bones and teeth. The phosphoric acid in cola is also a reason for claims that cola is harmful. The phosphoric acid in cola can dissolve the calcium in teeth to form calcium phosphate, leading to tooth erosion or cavities. Excess phosphoric acid in our bodies can deplete calcium ions that should be used to form bones, potentially causing osteoporosis, and calcium phosphate precipitation can lead to kidney stones. The concentration of phosphoric acid can vary slightly between different brands and types of cola, but it typically falls within a similar range (~ 10 mM) across the board. It’s worth noting that while regulatory agencies generally recognize phosphoric acid as safe when consumed in moderation, excessive intake of phosphoric acid-containing beverages has been linked to potential health concerns.

The acidity of cola, due to citric acid and phosphoric acid, allows it to be used for various purposes beyond just being a beverage. Multiple media have highlighted that cola can remove rust or clean stubborn toilet stains. While cola is quite acidic, many commercially produced beverages have a pH below 3.0. It is known that beverages with a pH lower than 4 are a significant cause of tooth erosion, aside from pathogens. Considering research findings that over 90% of commercially available beverages have a pH lower than 4, it appears that cola is not the sole culprit in beverage-related dental issues.

I’ve used cola as an example to explore the ingredients responsible for the tangy and refreshing taste of carbonated beverages and their properties. Despite the amounts and characteristics of these acids, it may seem like there shouldn’t be significant health concerns if one does not consume much of them. So why do many believe that cola and other sodas are bad for you? To find the answer, let’s explore the other ingredients commonly found in carbonated beverages.

References

- Skilling, Ask Tom: Does carbon dioxide released by soft drinks contribute to global warming?, Chicago Tribune, 2019. 02. 12

- Weinraub and Kelly, How ethanol plant shutdowns deepen pain for U.S. corn farmers, Reuters, 2019. 12. 13.

- Kelly and Baertlein, Beer may lose its fizz as CO2 supplies go flat during pandemic, Reuters, 2020. 04. 18.

- Reddy et al., J. Am. Dental Assoc. 2016, 147, 255

- http://www.nof.org/patients/treatment/nutrition/

- http://www.dietandfitnesstoday.com/phosphorus-in-orange-juice.php

- Larsen, (2009) ‘Erosion of teeth’ in Dental Caries: The Disease and Its Clinical Management. 2nd ed, Blackwell Munksgaard

- https://www.coca-colacompany.com

- Glusker, The Story of Mexican Coke Is a Lot More Complex Than Hipsters Would Like to Admit SMITHSONIAN magazine, 2015. 08. 11.

- Wiebe et al. BMC Med. 2011, 9, 123

- https://www.fda.gov/food

- WHO, (2015) Guideline: Sugars intake for adults and children, WHO

- Koob and Simon, J. Drug Issues, 2009, 39, 115

- Volkow et al. Transl. Psychiatry, 2015, 5, e549

- Mayo Clinic Staff, Caffeine: How much is too much? Mayo clinic, 2020. 03. 06

- https://www.math.utah.edu/~yplee/fun/caffeine.html

- Drayer, What makes soda so addictive?, CNN health, 2019. 10. 28.

- Vos et al. Circulation, 2017 135, e1017

- Castle, Caffeine: a Growing Problem for Children, US News, 2017. 06. 01.

Leave a comment